Victims of administrative carelessness are discovering, sometimes very belatedly, the despoliation they have suffered. The institutions must pay!

The retirement pension is one of the branches of Social Security, designed to enable people to reap the rewards of their work once they are no longer in employment. By way of ‘safety net’, it includes a mechanism designed to guarantee, if necessary, a better pension than that calculated on the basis of the worker’s professional path and to protect the weakest against the risk of finding themselves in need: this is the minimum subsistence rule.

The legal basis for the pension scheme of the EU institutions is to be found in the Staff Regulations. The unmissable gateway to retirement pensions is Article 77 of the StaffRegs. This provides for two alternative methods of calculating the pension:

- one (2nd) based on the accrual of pensionable years (including those from a transfer) and the last basic salary;

- the other (4th ), with years of service being the only variable:

4% x [minimum subsistence figure] x [years of service], the minimum subsistence figure being defined as the basic AST 1/1 salary.

Both calculations will have to be made in view of fixing the pension rights upon retirement, even if 4th para. only affects low salaries and short AST careers. It is the best of the two results that will determine the amount of the pension.

However, at the critical moment, when the person concerned must decide whether or not to transfer his or her rights acquired under a national scheme to the EU scheme, Article 77 has been bypassed! 4th para. fell out of sight. Whether or not to transfer is an option that the Staff Regulations reserve to the person concerned. Still, the administration took the option of 2nd para. and went straight on to land on the details of implementation of the transfer, while in some cases it explicitly advised transferring. This immediately resulted in the loss of the national pension.

This is where the ordeal begins for all those who were not informed in good time by the relevant department of the existence of the minimum subsistence rule. ‘In good time’ means before signing ‘for agreement’ the transfer IN proposal addressed to them by the administration.

The newcomer, often with a modest level of relevant knowledge in the cases that interest us, was deemed to be familiar with the StaffRegs, unlike the officials in the department in charge, who, due to their workload, could not find the time to inform them of the very existence of the minimum subsistence rule.

As if ignorance of the existence of the minimum subsistence rule wasn’t enough, the wording of the official letters from the administration added to the confusion: “the additional pensionable years to which this transfer would entitle you” or: “These pensionable years will be credited to your account with the Union pension scheme“.

Could the reader of these letters deduce from this that these ‘additional pensionable years’ would only exist at the time of the transfer, without any guarantee that they would also be reflected in his or her pension when it would be paid out? In reality, there are ‘additional pensionable years’ (on entry) that are “not taken into account” (when the pension is paid out).

This is a blatant case of breach of administrative duty and of the Union’s liability: a path strewn with procedural pitfalls and dishonourable for the institution. The search for remedies has nonetheless turned towards a remedy that is – in theory at least – non-contentious and not linked to any illegality or fault in the institution’s conduct, but to the idea that the Union was itself unjustly enriched to the detriment of those who brought the funds in. In other words, since the Union had appropriated the capital that the interested parties had transferred IN without providing any consideration, it should return that capital.

The case law in this area brightened up, only to plunge back into darkness immediately afterwards.

The Barroso Truta judgment: a great leap forward, but an isolated one

In our publication Pension rights: transfer or not? 8 January 2019, we set out the developments up to the judgment of the General Court (Appeal Chamber) of 18 September 2018, Case T-702/16 P, Barroso Truta and Others -v- Court of Justice.

A landmark ruling, one that cleared the way. Unfortunately, the ground that had been cleared subsequently fell again fallow.

Two diametrically opposed philosophies

To understand the nature of this judicial saga, we need to go back to the principles and values that underpin the two lines of argument.

A. A body of case law is converging to ensure that the pension rights acquired throughout a person’s professional path, in the EU system and in national schemes, are reflected in their pension(s).

- The system of transferring pension rights was set up in favour of officials and other servants in order to guarantee the EU the best possible choice of qualified staff (Commission -v- Belgium judgment, case 137/80). A transfer bound to work against the person concerned is contrary to the purpose of the system.

- In the absence of a transfer, the years of work completed in a European institution are added to the pensionable years acquired in a national scheme, in order to establish the right to a retirement pension, which will be calculated pro rata to the period of affiliation to the national scheme (judgment in My v ONP, C-293/03, order in Ricci and Pisaneschi v INPS, C 286/09 e.a.). Therefore, non-transferred pensionable years are never lost.

- In Kristensen v Council, Joined Cases T-103/98 and Others, given that the pensionable years added at the time of a transfer IN were capped at the actual period of affiliation, the part of the capital not added in pensionable years had to be paid back to the person concerned in the form of a pecuniary surplus. Unlike this case, in which the unjust enrichment in favour of the Union is immediately quantified and repaid, in the Barroso Truta and subsequent cases the enrichment can only be quantified with accuracy when the pension rights of the person concerned are settled. In fact, the timing is simply different.

The rule introduced by the Kristensen judgment, based on the principle common to the legal orders of the Member States of prohibiting unjust enrichment, which is applicable even without being provided for in the Treaties, was subsequently crystallised in the General Implementing Provisions (GIP) of the institutions. The Barroso Truta judgment suggested that a provision along the same lines be adopted to cover cases such as those at issue.

B.The opposite approach is that which denies the global vision of pension rights and confines itself to defending the EU-budget.

Budgetary alarmism, brandishing among other things the risk of opening Pandora’s box to those whose pension rights exceed 70% of their basic salary. A hypothetical claim that cannot be defended, since no error can be excused when it comes to knowledge of the existence of the 70% ceiling.

The motto DON’T PAY has become a pseudo-legal principle, and those who claim their rights are seen as profiteers. The victims of incompetence, sometimes even malice, on the part of those in charge, will never recover from the trauma of the despoliation they suffered by putting a signature by which the product of their work went up in smoke.

While the intentions of the budget watchdogs are obvious, it is the method of demolishing the Barroso Truta ruling that is the most pernicious. This is not a mere reversal of case law. The change in the meaning of words undermines the judgment itself and other case law, by short-circuiting, moreover, the interpretation and application of provisions of the StaffRegs and the GIPs, so as to deprive the legal framework of its clarity and turn it into a Tower of Babel.

The phrase “the share of the capital of his national pension rights transferred to the European Union pension scheme of which account will not be taken when that person’s pension rights are calculated” has apparently come to mean “pieces” of pension rights which, when transferred, have fallen by the wayside. Had this been true, the remedy to it would have been simple: In the event of an error or omission, the amount of pension may be calculated afresh at any time on the administration’s own initiative (art. 41, Annex VIII). As long as there has been no error or omission, the DON’T PAY school of thought considers that everything is in order and that there is nothing to repay. If the calculations were made in accordance with the rules, the amount transferred IN was, in their view, taken into account, under 2nd para., even though it had no effect on the pension, which was determined on the basis of 4th para.

-t-

The saga of transfers which have gone down the drain is not over. Victims of administrative carelessness are discovering, sometimes very belatedly, the despoliation they have suffered. The institutions must pay!

The Commission has belatedly drawn the attention, on its My IntraComm website, to the existence of the minimum subsistence rule. While the minimum subsistence rule is inspired by noble intentions, the mechanism for its implementation calls for appropriate reconsideration.

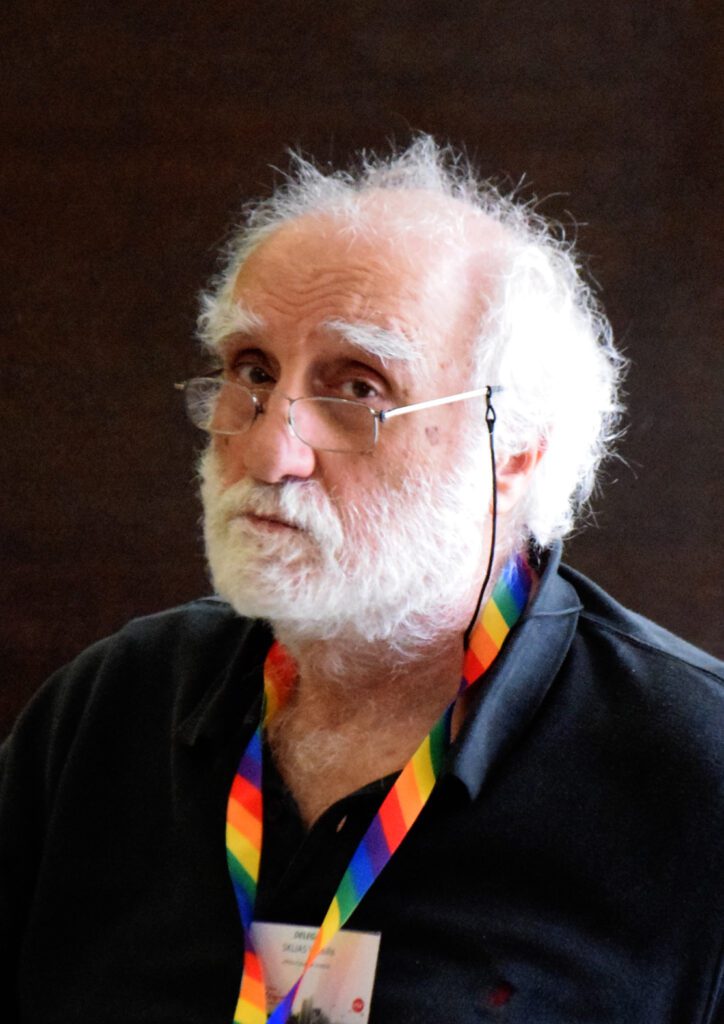

Vassilis SKLIAS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

General Secretary of EPSU- CJ and member of Committee Federal USF

Michel WEISER

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Member of EPSU-CJ